The first and best impression of your house.

My house was built in 1917; it’s a quaint little cottage with a few interesting details. During the Energy Crisis of the 1970s, the owner was sold every possible energy-saving improvement, such as the horrific passive solar water heating system. Years after its removal, I’m still digging strange pipes out of the attic. The worst indignity visited upon my home, aside from the 10-inch to the weather aluminum siding, was the attack of the Replacement Door and Window Guy.

When I bought the house, there was one of those steel, energy-efficient front doors secured with crude spacers to make it fit the original opening. It was horrible, and I ripped it out with cathartic glee. I had, in my basement full of old house parts, a c.1900 quarter-sawn oak front door that fit the old jamb without planing. Is it as weather-tight and energy efficient as the steel one? NO! And I don’t care! I’m willing to cough up a few extra bucks a year to have the appropriate front door: I’ll do without air conditioning to make up for it.

I’m not alone; countless old houses have had their historic doors yanked out during the past 30 years in the name of energy savings or because the owner couldn’t be bothered with a proper repair. A painful fact: no matter how good your restoration is; the wrong front door is as glaring as a big piece of spinach stuck between your teeth.

I’m not alone; countless old houses have had their historic doors yanked out during the past 30 years in the name of energy savings or because the owner couldn’t be bothered with a proper repair. A painful fact: no matter how good your restoration is; the wrong front door is as glaring as a big piece of spinach stuck between your teeth.

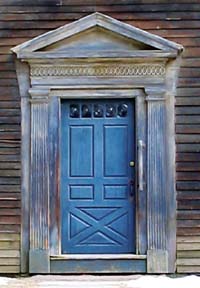

The ornamentation and design of our front doors has never been haphazard or an afterthought; they are intended to be our visitor’s first impression as they stand there, shivering and waiting for us to let them inside. As you travel the older roads of New England, you will invariably see a plain house where the builder splurged on a highly stylish and ornamental front door and surround. These are integral to the historic design of the structure, and should been retained, whenever possible.

There is an exception to this rule; many 18th and 19th century houses were “updated” during the late 1880s-1910 with a combination of Queen Anne and Colonial  Revival touches. The most common of these is the addition of a wrap-around porch instead of the smaller threshold or portico that was previously used. This updating might consist of a simple porch addition, or could totally affect the interior and exterior of an antique home. Newel posts and mantles were often replaced with the then-contemporary styles, and yes, so was the front door, which by now had had 50-100 years of kids slamming it shut.

Revival touches. The most common of these is the addition of a wrap-around porch instead of the smaller threshold or portico that was previously used. This updating might consist of a simple porch addition, or could totally affect the interior and exterior of an antique home. Newel posts and mantles were often replaced with the then-contemporary styles, and yes, so was the front door, which by now had had 50-100 years of kids slamming it shut.

This scenario puts the old house enthusiast in a quandary: how does one approach subsequent now-historic remodelings of their structure? The best course of action is to follow the lead of house-museum professionals; choose a period of interpretation. Let’s say you’ve got a Greek Revival from the 1830s and someone added a sweeping porch festooned with gingerbread embellishments around 1890. At the time, they also replaced the front door with a Colonial Revival Dutch door hung with big brass strap hinges. Unless you are willing to rip off the entire porch and restore it to the period of interpretation of 1834, I’d leave the existing door, as both are in keeping with this style.

Of course, we tend to be a little parochial in our interpretations: while being perfectly content to leave an 1890s remodeling be, I would probably not want to preserve a 1960s flush door with those little intersecting-circle windows. I know it’s short-sighted, and eventually everything becomes historic, but you have to draw the line somewhere, and for me, it’s World War I and the advent of Modernism.

Of course, we tend to be a little parochial in our interpretations: while being perfectly content to leave an 1890s remodeling be, I would probably not want to preserve a 1960s flush door with those little intersecting-circle windows. I know it’s short-sighted, and eventually everything becomes historic, but you have to draw the line somewhere, and for me, it’s World War I and the advent of Modernism.

Recently, I spent a chilly Saturday walking around Suffield, CT and Historic Deerfield, MA in search of Appropriate Doors, and found some stellar examples. The earliest one, which I found in Deerfield, is an ancient two-plank number with exposed nail-heads. Historic Deerfield, for those who haven’t made the pilgrimage, is a veritable textbook of early architectural styles. There are wonderful crossbuck and paneled doors, both single and double, surrounded by intricate pilasters and pediments. It’s a delight to wander about and study the various periods in context.

The earliest one, which I found in Deerfield, is an ancient two-plank number with exposed nail-heads. Historic Deerfield, for those who haven’t made the pilgrimage, is a veritable textbook of early architectural styles. There are wonderful crossbuck and paneled doors, both single and double, surrounded by intricate pilasters and pediments. It’s a delight to wander about and study the various periods in context.

Another educational meandering is along Main Street through the center of Suffield. There’s a Greek Revival with a recessed portico whose door is emblazoned with tiny anthemions, several bold Second Empire mansards with heavily molded spilt doors illuminated with original wheel-etched glass, and charming turn of the century doors of every variation. I’d wait until spring, though, when the owners remove their storm doors which obscure so much of the detail. The highlight of the trip is the Phelps-Hatheway House, which still has its original outbuildings and 1802 wallpapers.

“Alright,” you say, “You’ve convinced me. I’m going to keep my drafty original door, because I love living in an old house and a little bit of fine snow blowing in now and then doesn’t bother me one bit.” It’s really not that bad; folks have always had to deal with heating and weather-stripping issues. It’s not like the Victorians enjoyed cold drafts; they hung heavy curtains known as portieres in every doorway to contain precious heat.

bit.” It’s really not that bad; folks have always had to deal with heating and weather-stripping issues. It’s not like the Victorians enjoyed cold drafts; they hung heavy curtains known as portieres in every doorway to contain precious heat.

As with historic window sashes, there are ways of making an old door weather-tight with careful weather-stripping and adjustments. The first step is making sure that hinges are working properly, and more importantly, that the lock and strike-plate are set up to close the door as tightly as possible. There are many forms of mechanical weather-stripping that will reduce airflow, and if you have a glass panel or sidelights, caulking them and perhaps adding a second layer of glass will help as well.

Storm doors obviously add a huge amount of protection, but finding an architecturally sensitive one will take effort, and of course, more money than the lumberyard variety. Some of these are designed to have the glass panels drop out and swap with screen panels. For those with early homes, you can use the louvered doors that look like elongated shutters backed with Plexiglas panels for winter use.

All of this sounds highly involved, but once it’s set up, installation becomes a simple autumnal ritual. It takes more effort to execute these old house touches, but you’re living one by choice; if energy-efficiency and function were your sole measures of selecting a structure, you’d be in a condo.

Dan Cooper has been working on old houses for over 20 years, and also writes for Old House Interiors, Period Homes, Cottages and Bungalows amongst other magazines on the subject of architecure, antiques and design.